Arrival

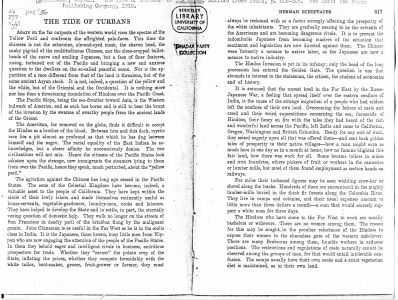

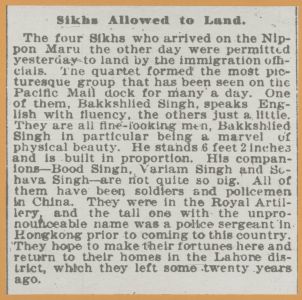

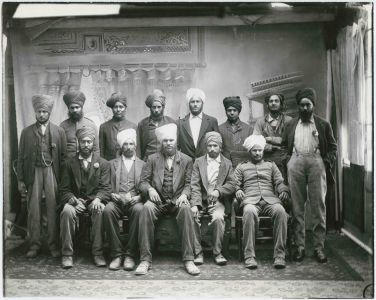

On April 6, 1899, the San Francisco Chronicle announced the arrival of four Sikh men who were allowed to enter the United States in San Francisco. This is the first record of South Asian pioneers in California. The author admired the Sikh men for their strength and physical beauty, but he struggled to pronounce their names. The positive description of the Punjabi pioneers in this article was rare; over the next decades California newspapers were hostile, reflecting and spreading the growing alarm about the new arrivals.

Who Were the Early Punjabi Pioneers?

The early South Asian pioneers were primarily men from the British Indian province of the Punjab. They predominantly came from farming backgrounds in a region that had only recently been annexed by the British. The Punjab was a powerful Sikh state until its annexation by the British in 1849. Many of the early pioneers had served in the British army and police in India and across the British Empire before coming to the US, primarily via Canada. The Punjabi pioneers left India to secure a better economic future, especially since many found it increasingly difficult to secure land in the Punjab in the late nineteenth century. The Punjabis also possessed a spirit of adventure. The Sikhs had seen the world on their tours of duty in the British military, and the Sikh religion did not prescribe religious taboos against leaving India.

More

California At the Turn of the Twentieth Century

It is helpful to approach the early history of South Asian pioneers within the broader historical context of the transformation of agriculture and the long-standing Asian immigration in California. Over the course of the late nineteenth century, the discovery of gold in 1848 transformed California from a pastoral outpost into a major world center for mining attracting large numbers of miners from around the world. Gradually California developed a corporate, capital-intensive system of agriculture that required a large farm labor force. By the time the Punjabis arrived in California at the turn of the twentieth century, public opinion and federal and state policies were turning against Asian immigrants from China, Japan and Korea. In response to the success of Japanese farmers in particular, a reactionary wave of discriminatory laws were passed, including California’s Alien Land Laws in 1913, 1920, and 1921. These laws barred “aliens” who were ineligible for US citizenship from leasing or owning agricultural land.

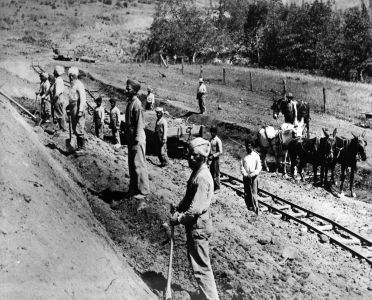

Growth of Punjabi Migration & Early Contributions

The Punjabi pioneers were far fewer in number than other Asian immigrants. The peak immigration of the early pioneers occurred between 1907 and 1910 with about 7,000 people arriving in the US during this early period. Almost 90 percent of the early pioneers were Sikhs, and the remaining 10 percent were Muslims with only a small number of Hindus. The Punjabis initially entered North America in Vancouver, Canada, on board ships from Hong Kong and Shanghai. As restrictions to South Asian immigration increased in Canada, the Punjabi pioneers headed south to the US to work in the lumber mills and railroads in Washington, Oregon, and California. About two thousand Punjabi pioneers worked on the Western Pacific Railway along a 700-mile road stretching from Oakland to Salt Lake City that passed through the Sacramento Valley. They also gravitated towards farming, making early contributions to the growth of California’s agriculture — they helped initiate rice farming in the northern Sacramento Valley and established cotton growing in the Imperial Valley. They grew other large cash crops, such as peaches, grapes, pears, apricots, almonds, beans, potatoes, almonds, celery, asparagus, and lettuce mainly in the Sacramento, San Joaquin, and Imperial Valleys in California, but also throughout western North America. The Punjabis quickly transitioned from farm laborers to landowners. In 1920, the Punjabi pioneers owned 2,099 acres and were leasing 86,340 acres of farmland, mainly in the Sacramento, San Joaquin, and Imperial Valleys. The first Sikh temple was founded in 1912 by the Pacific Coast Khalsa Diwan Society in Stockton. Most incredibly, the Punjabi pioneers waged a war against the British Empire from their headquarters in San Francisco in a worldwide political movement known as the Gadar (revolutionary) party.

Angel Island

Established in 1910, Angel Island Immigration Station in the San Francisco Bay — the Ellis Island of the West — was the main point of arrival for Asian immigrants into the United States in the early twentieth century. Over the next few decades, hundreds of thousands of people from China, India, Japan, Korea and many other countries were stationed, quarantined, and processed at this immigration facility. Approximately 7,000 Punjabi pioneers passed through Angel Island, often enduring humiliating questioning by immigration officials, invasive health examinations, and sometimes lengthy periods of detention.

Backlash

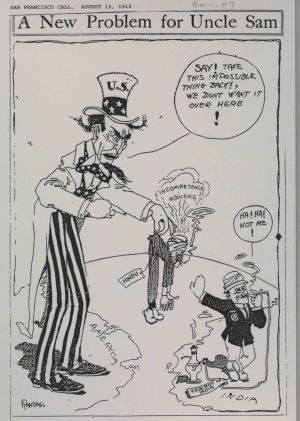

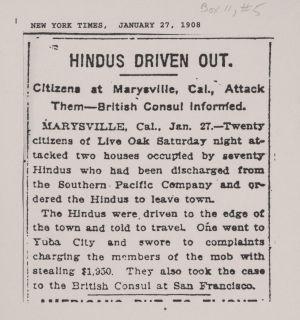

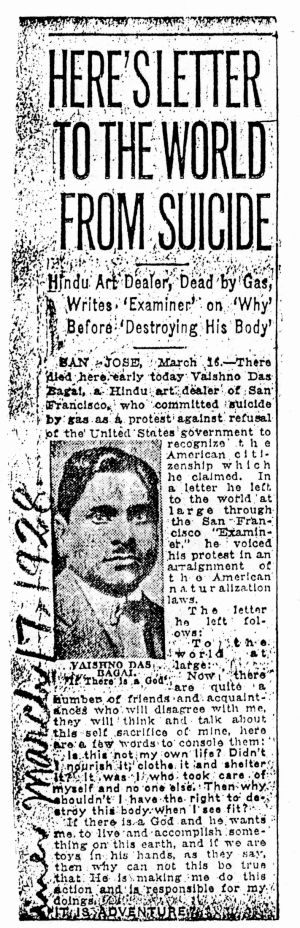

Despite the fact that the vast majority of the South Asian immigrants were Sikhs, the early pioneers were almost universally called “Hindoos” and “Ragheads” in California until the 1980s — terms that were meant as racial slurs to signify the new arrivals’ undesirability, foreignness, and inability to assimilate into Anglo-Christian American culture. Violence against turban-wearing Sikhs was spreadheaded by many political and labor organizations. The Asian Exclusion League obtained the support of the American public, political parties, and the press to exclude them from the US. Amidst growing labor unrest, there were riots against the Punjabis in many rural towns along the West Coast, including Bellingham, Washington (1907). There were several riots against the Punjabis in northern California in Marysville and Live Oak near Yuba City and in Fair Oaks near Sacramento in which white residents attacked and drove “Hindoos” out of town. Although the number of South Asian pioneers in California was small compared to other immigrant communities at this time, California newspapers sounded the alarm about the so-called “Hindoo invasion” and the “Tide of Turbans,” and journalists generally defended attacks on the Punjabi community. During the economic downturn, labor unions vociferously argued that so-called cheap Asian labor would undercut the wages of white workers and undermine American values more broadly.

The “Asian Barred Zone” Act of 1917

Five years of organized violence and racial hostility against the Punjabi pioneers (1907-12) with no help from the Indian government left many feeling that they were stateless without basic civil rights and that the absence of a free India left them vulnerable in the US. In part as a response to racism in the US, the early pioneers formed the Gadar Party in 1913 and many returned to India to fight to overthrow British rule. Dozens were martyred when they returned to India. Other pioneers stayed in the US, and applied for citizenship, bought or leased land, and saved money in order to bring their families to join them. Their efforts were circumscribed by the tightening of anti-Asian laws and growing hostility. The Asian “Barred Zone” Immigration Act of 1917 stopped almost all Asian immigration, creating enormous implications for Punjabis and their families. Most Punjabis who arrived in the US were men, many of whom had left their wives and children in India. The South Asian pioneers had one of the most unbalanced gender ratios: there were only 100 women per 1,572 men in 1930 (See Karen Leonard, Making Ethnic Choices). In Yuba City, there were only four Punjabi women prior to World War II. The exclusionary immigration policy meant that Punjabi families were separated for decades until the laws changed in the late 1940s. The severity of these exclusionary laws was somewhat mitigated by the ambiguous place of Punjabis within California’s racial hierarchies — in practice, discriminatory laws about land ownership and marriage were applied unevenly depending on whether a county clerk perceived a pioneer as belonging to the white race or not.

SOURCES:

Anderson, Erika Surat. “Turbans” PBS Documentary, 2012.

Jensen, Joan M. Passage from India: Asian Indian Immigrants in North America (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1988).

Kang, Jasbir Singh. “Punjabi Migration to the United States: A Story of Great Tenacity,” Sikh Foundation, http://www.sikhfoundation.org/PunjabiMigration_JSKang.html

Kang, Jasbir Singh. “Punjabi Migration to United States: The Story of Americans Who Came From the Land of Five Rivers Known as Punjab,” Becoming American: The Story of Pioneer Punjabis and South Asians (Yuba City: Punjabi American Heritage Society, 2012), 12-14.

La Brack, Bruce. The Sikhs of Northern California (New York: AMS Press, 1988).

Leonard, Karen. “Punjabi Farmers and California’s Alien Land Law” Agricultural History 59:4 (October 1985), 549-62, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3743757

Leonard, Karen Isaksen. The South Asian Americans (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1997)

Metcalf, Thomas R. Imperial Connections: India in the Indian Ocean Arena, 1860-1920 (Berkeley: University of California, 2007).

Puri, Harish. Ghadar Movement: Ideology, Organization and Strategy (Amritsar: Guru Nanak Dev University Press, 1983).

Ramnath, Maia. Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, 1907 Bellingham Riots in Historical Context (http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/bham_history.htm)

Singh, Jane. South Asians in North America: An Annotated and Selected Bibliography, Occasional Paper No 14 Berkeley (Berkeley, Center for South and Southeast Asia Studies, 1988).

South Asian American Digital Archive, https://www.saada.org/

Street, Richard Steven. Beasts of the Field: A Narrative History of California Farmworkers, 1769-1913 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004).

Vaught, David. Cultivating California: Growers, Specialty Crops, and Labor, 1875-1920 (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

Less