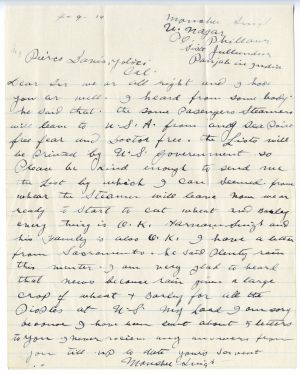

Pierce Ranch Almond Huller. Pierce Family Papers, Special Collections, University of California, Davis Library.

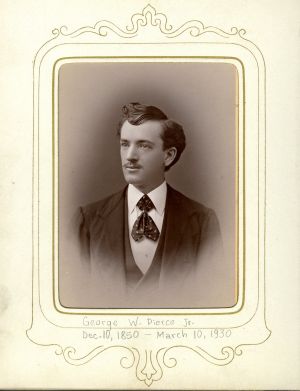

Munsha Singh (September 27, 1885 – September 18, 1971) is an obscure figure in the history of South Asian pioneers. What little is known about his life comes almost exclusively from the writings of his employer, George Pierce, Jr., an influential horticulturalist in Davis, CA. Although he is best known for successfully lobbying to locate the University of California’s Farm School in Davis, Pierce also wrote what is likely the first record of Punjabi farm workers in California in 1907. Munsha Singh became a crucial part of Pierce’s farm operations. In the midst of a severe labor shortage during World War I, Pierce was so desperate to bring Munsha Singh back to his ranch to oversee his almond harvest that he paid for his ship ticket from Hong Kong to California. But when Munsha Singh arrived in San Francisco, he was detained at the Angel Island Immigration Station and threatened with deportation due to a new law barring Asian immigrants from entering the US. Pierce’s diary recounts his extensive efforts to secure Munsha Singh’s release in time for the almond harvest.

Early Years in Davis

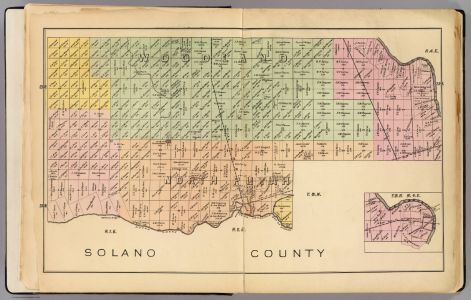

George Pierce, Jr.’s diaries and accounts are significant primary sources in the origins and development of farm labor relations in California at the turn of the twentieth century. Like other white orchardists, Pierce described the laborers on his farm, most of whom were transient, by first name and collectively as “boys.” Similar to most white Americans of his time, he viewed non-whites as inferior. Finding it difficult to secure reliable white workers at reasonable rates, he employed Chinese and Japanese farm workers. However, when four Sikhs arrived at the Pierce farm in the spring of 1907 looking for work, Pierce was pleased by their willingness to work for $1.25 per day and by their strong physical appearance. The Sikhs accepted the work: Pierce’s wages far exceeded those in India at the time for similar work (10 to 15 cents per day). Initially, Pierce hired the Sikhs to perform manual jobs, such as digging irrigation ditches, sawing and stacking wood and hauling manure. Munsha Singh returned the following winter and soon earned Pierce’s confidence. Mr Singh quickly became an integral part of Pierce’s success. He served as the contractor who recruited a steady supply of Sikhs from Yuba City (50 miles north of Davis in the northern Sacramento Valley), Sacramento and elsewhere, and consistently delivered profitable harvests. Pierce’s confidence in Munsha was shown in 1913 when he allowed Munsha to share the duty of operating the almond huller with him.

More

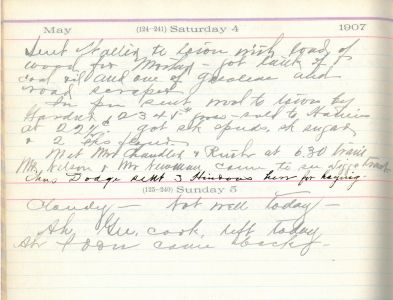

Pierce refers to the Sikh farm workers as “Hindoos” in his diary, even though the vast majority were Sikhs. White Californians almost universally used the term “Hindoo” to describe the South Asian pioneers; the term reflected the white population’s general view that the new immigrants were racially undesirable and unfit for US citizenship. In perhaps the first reference to Punjabi farm workers in California, Pierce records on May 4, 1907: “Chas Dodge sent 3 Hindoos here for haying.” During the spring and summer of 1908, his diary is filled with brief notations about the number of “Hindoos” who worked on his farm and the kinds of jobs they performed. A typical entry on April 14, 1908 reads: “Put two Hindoos to hauling gravel for headset on Fairfield ditch… they hauled 8 sacks cement to cement workers at Greene crossing.” Even though Munsha Singh became an integral part of Pierce’s farm operation, Pierce never learned his true name, referring to him variously as “Mousha,” “Monshee,” and other names.

Return to the US and Detention at Angel Island

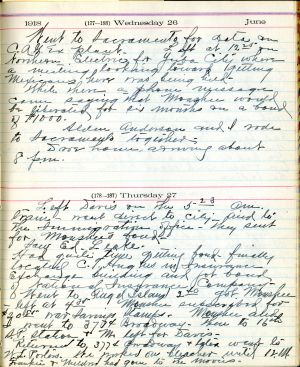

In December 1913, Munsha Singh suddenly quit his job on the Pierce ranch and returned to India, perhaps to join the Gadar movement to overthrow British rule in his homeland. In the fall of 1917, amidst an acute labor shortage, Pierce finally located Munsha Singh in Hong Kong and sent him a steamship ticket to return to California. When Mr Singh arrived in San Francisco, he was detained by federal authorities at Angel Island in compliance with the recent law that barred immigration from Asia, including India. Pierce went to considerable lengths to secure Mr Singh’s release, appealing to the federal commissioner, visiting him several times at Angel Island, and finally serving as his legal guardian to obtain a six-month bond for his release. On June 27, 1918, Pierce records in his diary the lengths he went to on the day of Mr Singh’s release: “Had quite time getting bond. Finally located C T Hughes in Insurance Exchange building and got bond of National Insurance Company. Went to Angel Island 2:40, got Monshee.” Having just spent four months in detention, Munsha Singh returned to work on the Pierce farm just two days after his release on June 29. He also hired 25 Sikhs to deliver a successful almond harvest that August.

Final Clues

The only other information available about Munsha Singh is derived from vital records. He was born and died in his native village of Nagar in the Jullundar district of the Punjab. He registered for the draft during World War I. According to US Census records, he remained a bachelor living with other Punjabi pioneers in Sacramento and on the Pierce Ranch in Davis. He attained US citizenship, and his passing in India at the age of 85 was noted by the American Embassy in 1971.

SOURCES:

Pierce Family Papers, Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. View the finding aid at: http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1c6002bw/

Street, Richard Steven. Beasts of the Field: A Narrative History of California Farmworkers, 1767-1913 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004.

Vaught, David. Cultivating California: Growers, Speciality Crops, and Labor, 1875-1920 (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

Vital Records

Less